The Battle for Zverograd, Part One

In the early 1930s the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union decided to engage in a bold experiment. A new modern city would be built in record time. Though smaller in size, it would compete with the most advanced great capitals of the world. This city would prove to the world that the Soviet Union could accomplish anything. Months were spent selecting the perfect location for this new city, as well as developing its name. It was finally decided that the city would be called Zverograd, and it would be built on the Caspian Sea, some 150 miles south of Astrakhan. It was built on the site of a medieval town, its name long forgotten, with wooden houses built on a hill surrounding an ancient Orthodox monastery. This small historic village was left intact in remembrance of the past, and in the surrounding lands the city of Zverograd started to grow.

Join the Return the Zverograd campaign from any part of the world!

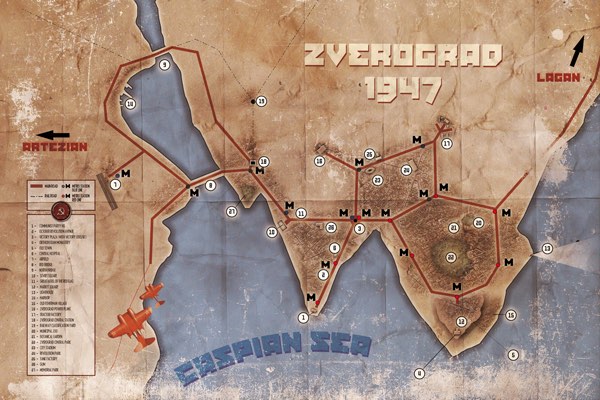

Map of the city of Zverograd

The best architects in the USSR gathered to plan the city. They decided to create a brand new metro system that would allow workers to quickly reach their factories and move around the city. They designed wide avenues to accommodate stunning parades. They planned modern roads and bridges to connect all parts of the city. They designed the central sewer system to support a much bigger population, expecting Zverograd to grow into one of the largest cities in all the Soviet Union.

Finally, only four years after determining its location, the first new residents of Zverograd began to arrive. They came from all over the country, lured by widespread advertising campaigns promoting the city as a modern paradise.

The first rumors began to spread in early 1941. Underground metro workers had “found something” while digging an expansion for a new line. They had no idea what it was, but described it as a huge underground structure, impervious to anything they could throw at it. The edifice had an eerie feeling about it, as though it didn’t belong down in the darkness beneath the city. An official team was dispatched from Moscow to investigate but, before any conclusion could be reached, German troops crossed the USSR’s western border and the war began. It would be years before the newly formed SSU would refocus its attention on the secrets beneath the once-great city, but now Zverograd has the full attention of the SSU - as well as their enemies.

Prelude

In late 1946 the top Axis spy network in the SSU learned of a massive alien structure below the city of Zverograd. Not only was it the largest discovery of its kind but wartime concerns prevented the SSU from mounting anything more than a cursory investigation of the site.

This intelligence came just ahead of the Axis’ planned global offensive. Within days, new orders were relayed to the Caspian sector: take Zverograd at any cost. To the operational planners in Berlin, the city seemed tantalizingly close, lying just over 30 kilometers behind a stable, unsuspecting front.

Unfortunately, Axis High Command did not anticipate the toughness of SSU resistance, nor did they consider an Allied response. Having learned of the Kremlin’s secret Vrill hoard, Allied leaders planned to join the fray once the Axis and SSU had sufficiently wearied one another with a war of mutual attrition. With forces stationed in friendly territory along the Caspian’s southern shore, the possibility of Allied involvement was quickly becoming a reality.

The assault on Zverograd was intended as a lightning thrust to secure a technological objective at the periphery of a much greater Axis effort to win the war. To the soldiers involved on all sides, it was a grim struggle to be endured. A precious few realized that the campaign had quickly become central to the fate of the world.

The Assault Begins

Axis Panzer IV-K en route to Zverograd

The first Battle of Zverograd, codenamed Operation “Hades,” began on the 1st of January, 1947. During the night of December 31st, 1946, Sturmpioniere units advanced beyond Axis lines to begin clearing a path through the minefields guarding the approaches to the city. Their mission was to open the way for shock units to race toward Zverograd, blasting through SSU lines. A similar scene was unfolding simultaneously on battlefronts as diverse as North Africa, Iceland, and Asia. As the SSU and the Allies would soon discover, the Axis global offensive had begun.

Before the Axis launched their offensive, the front to the west of Zverograd had been stable for nearly a year, with both sides occupying well-entrenched positions. In the final days of December, SSU troops on the front lines were the first to become aware of the presence of new Axis formations. When Operation “Hades” began, it was these units’ junior officers who first reported aggressive enemy action and roused local HQ’s, which then quickly mobilized second and third lines.

At 4:00 a.m. on January 1st, hundreds of German Nebelwerfers began firing their rockets into the frozen ground of the SSU entrenchments. Despite the early warning signs of the attack, SSU forces could not prepare an effective defense until it was too late. The sudden bombardment inflicted massive casualties among SSU ranks. The SSU counter- battery started half an hour later, targeting presumed concentrations of Axis troops.

E-100 - Axis Super-heavy Tank in 1947

At 5:30 a.m., the Axis assault started. The initial push from the north was made by the solid armored formations of the 33rd Special Duty Panzer Division, “NachtJäger.” At its spearhead were the heavy E-100s of the Schwer Panzer Abteilung 515, each one accompanied by Tiger II tanks or JagdLuther 75 walkers to guard their flanks.

From the south, the 2nd FußPanzer Grenadier Division, “Leibstandarte Erwin Rommel,” made its initial thrust using an elite combined force of Sturmgrenadiere units and Panzer KampfLäufers. After the initial shock, the 4th Blutkreuz Korps Kommando leapt into action, cutting off supplies and communications from behind enemy lines. The morale-eroding effect of squads of Zombies in a frontal assault again proved catastrophic to SSU defenders, and squads of Axis Gorillas crushed SSU strongpoints and destroyed artillery weapons.

SSU KV-3M 'Babushka' walker

Realizing that a full-scale assault was underway, the HQ of the 13th Red Banner Army informed the Stavka of the situation and proceeded to mobilize all of its reserves. The 1st Red Guards Motor Rifle Division was rushed to the front, their tanks carrying most of the soldiers of the 10th SSU Rifle Division. However, to protect them from artillery fire, these elite forces had been placed some 20 kilometers east of Zverograd, and were therefore almost 40 kilometers from the action when it started. The hope was to engage Axis forces in open terrain, well beyond the city’s outskirts, but they would arrive too late to prevent the attackers from reaching the city.

As Axis forces approached Zverograd, SSU troops guarding its airfield were ordered to detonate explosives with the intent of crippling the landing strip, rendering it unusable without heavy repairs. Before they could act, they were slaughtered in their barracks by several squads of Axis Gorillas that had managed to infiltrate the airfield during the night. Reports of an enemy U-Boat lurking near the shoreline just before the incident remained unconfirmed.

On the northern flank, the “NachtJäger” quickly occupied Zverograd’s harbor and rushed toward North Bridge. Gaining access to the city’s east side, and then its center, was of the utmost importance to the Axis forces, as was taking Red Bridge to the south–without this bridge the assault would be stopped naturally by the Caspian Sea.

At the first light of dawn, the Luftwaffe launched waves of assault aircraft toward the city. Zverograd’s defenders were massed west of the city center, most of them routed, waiting for the first units of the 13th Red Army to arrive before launching a counteroffensive. As the first Stukas and Hortens started bombing the city, SSU soldiers looked to the sky: where was the 2nd SSU Air Fleet? At the regional HQ of the Air Fleet, 60 kilometers north of Zverograd, SSU staff had committed one of the worst blunders of the battle. In the chaos following the news of the Axis advance, a miscommunication had sent most of the SSU’s air support to another theatre, far from Zverograd.

As a result, the Luftwaffe had a momentous day. Flying mostly unopposed, Axis planes had only to worry about the antiaircraft emplacements within the city. The SSU’s new heavy IS-5 antiaircraft tanks were still more than 10 kilometers away, unable to prevent fire from raining down on Zverograd’s defenders.

When the SSU elite forces finally reached the city, significant damage had already been done. Axis forces had gained a strong foothold in the western part of the city center, the railways to the north had been blocked off, and Axis tanks and walkers had some of the city’s largest factories surrounded, making the battle even more difficult than the reinforcing SSU units had expected. With Axis forces firmly entrenched, gritty, guerrilla-style urban combat ensued, with neither bloc gaining a clear upper hand. By this point, most of the city’s population had fled to the east; only the factory workers remained, grimly determined to help their homeland’s army.

Allied invasion of Zverograd

When news of the attack on Zverograd reached the Ninth Allied Army HQ in Tehran, the Allies quickly set their own plans in motion. The Allies were also under attack from the Axis’ global assault, with most of the offensives occurring in Libya and Northern India. However, Tehran was relatively untouched. From their intelligence network, whose reach extended into the upper ranks of SSU leadership, Allied commanders had learned what few facts were available about the secret below Zverograd.

Though Zverograd was removed from more central battlefronts, Allied forces were available in the Middle East. Opportunity had arisen for the Allies to make great strides in their own Vrill program while the Axis and the SSU fought in the streets of Zverograd. An aggressive reconnaissance expedition was quickly planned under the supervision of the 4th Marine Division.

In addition to these tough soldiers, the Ninth Army found another unengaged asset in the form of the newly- assembled 8th Ranger Battalion of the Allied Army. All that this elite formation lacked was a proper commander. General McFarland, head of the Ninth Army, had heard that ASOCOM was looking for an excuse to redeploy renowned war hero Joe Brown in a different theater. His frequent clashes with Blutkreuz operative Sigrid von Thaler in Antarctica had been deemed “unproductive.” McFarland put in his request, which received a prompt and enthusiastic approval from ASOCOM, and Brown was hastily transported across the world to his new command.

During this transition, the Marines were busily preparing for the expedition, and an operational plan was in place by the first days of February. They were to land on the eastern shore of Zverograd’s Old Town district in the dark of night during the next new moon. The beach itself was quite small, but Marine scouting teams reported that the nearby caves were defensible and sheltered from enemy artillery. Most importantly, this stretch of coastline was undefended by the SSU, as they were too busy fighting the Axis inside Zverograd.

On March 9th, the hastily assembled Allied Caspian task force arrived at Zverograd. Though difficult, the early stages of the landings were successful: the 4th Marine Division infantry and walkers from the 3rd Cavalry Division swiftly occupied a substantial section of the narrow beaches. At the same time, the 8th Ranger Battalion, now renamed “Brown’s Roughnecks,” cleared Zverograd’s lighthouse of any resistance, securing an excellent position from which to direct artillery fire toward the city.

Now facing attacks on multiple fronts, Zverograd’s embattled SSU forces find themselves in the direst of situations.

Go on to Part 2.

Join the Return the Zverograd campaign from any part of the world!